At Coinbase, we encounter numerous personalization and ranking challenges that can be significantly improved with Machine Learning. However, the traditional workflow creates a bottleneck: each new modeling use case typically requires two resource-intensive steps: building a bespoke feature set and training a custom model from scratch.

Scaling with a small team is unsustainable if every new problem requires a dedicated end-to-end effort. To solve this, we introduced User Foundation Models. By training a single model on sequence features that encompass a broad range of user activity, we create a versatile user representation that can be reused across dozens of downstream applications.

The "Universal" Feature Set

In the standard modeling workflow, engineers hand-craft feature sets specifically designed to capture information relevant to a target variable. Over time, this has resulted in Coinbase maintaining thousands of distinct features, each optimized for a specific task but offering limited generalizability across different personalization problems.

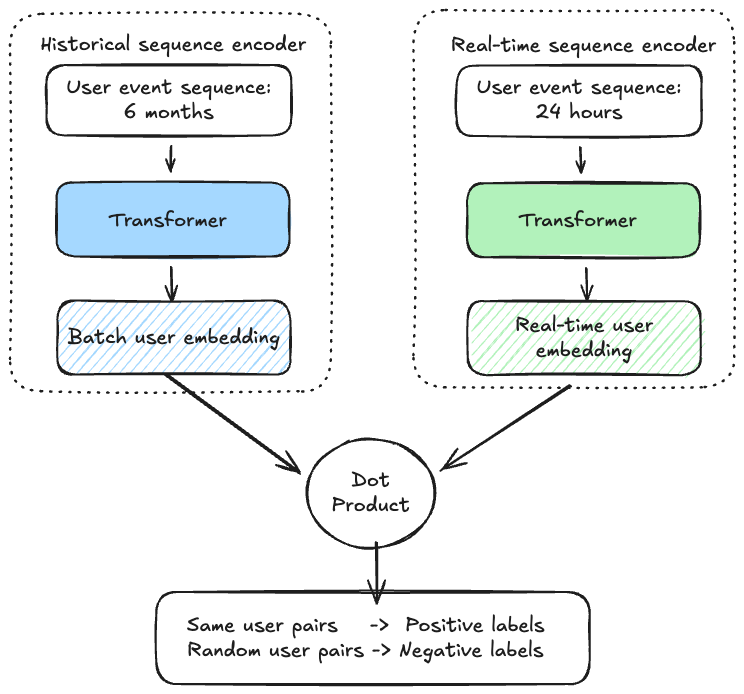

Instead of hand-crafting features for every model (e.g., "number of views of Bitcoin price chart in the last 7 days"), we construct a single long-range sequence containing nearly every user interaction over the last several months. We combine long-range historical data (batch computed) with real-time streaming actions (last 24 hours) to ensure the representation is up-to-the-minute fresh. Note that the “tokens” which comprise these sequences do not contain any personally identifiable information (PII).

Under the Hood: Self-Supervised Learning

We feed this user action sequence into a Transformer-based two-tower architecture. The key challenge: we want to train a model that learns a general-purpose representation of users—not one narrowly optimized for a specific prediction task like "will buy Bitcoin." Specifically, we train the model on a Sequence-Pair Classification task. The training process uses a balanced sampling procedure to ensure the model learns robust representations:

Positive Pairs: We sample two distinct activity sequences from the same user (with non-overlapping time windows).

Negative Pairs: We sample sequences from two different users, randomly selected.

Balanced Training: The model is fed an equal mix of positive and negative pairs.

Objective: The model must determine whether the two sequences belong to the same user.

By forcing the model to solve this matching problem, it learns to generate a high-dimensional vector (embedding) that captures a rich behavioral representation of the user.

Methods for Leveraging Foundation Models

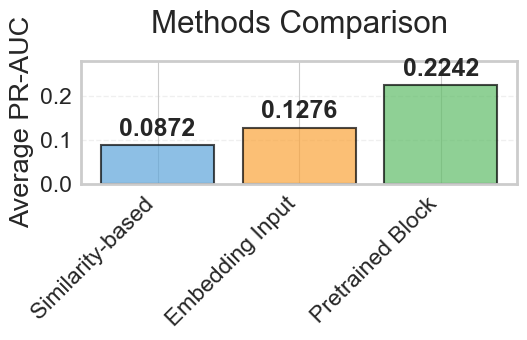

We evaluated three different approaches for applying these user representations to supervised downstream tasks. Consider a practical example: targeting users for a notification about a newly listed token. Given a set of users who engaged with the notification (positive labels) and those who did not (negative labels), we aim to identify additional users likely to be interested. The three methods differ in how they incorporate the foundation model into the prediction pipeline:

Direct Similarity (Zero-Shot/Few-Shot): This method requires no additional model training, we generate embeddings for users from the penultimate layer and simply use cosine distance to find users similar to those whom we have labels for. In practice we find that taking a weighted difference of positive and negative labelled users performs better than using only those users with positive labels.

Static Embedding Features: The embeddings are used as pre-computed, static inputs to a supervised deep learning model. These could be the sole input to the model, or in conjunction with other features.

Pre-trained Initialization (Fine-Tuning): The most powerful approach involves using the foundation model as a pre-trained architectural block within a larger model. By initializing with our self-supervised weights and then fine-tuning on the specific task, the model adapts the representation to the exact problem space. Our benchmarks consistently show this method yields the highest performance.

Benchmarking Self-Supervised Representations

A fundamental challenge with self-supervised learning is evaluation: how do you measure the quality of a representation that wasn't trained for any specific task? Standard classification metrics on the training objective (e.g., accuracy on same-user vs. different-user classification) don't tell you whether the learned embeddings will actually be useful downstream.

Our solution is a multi-domain evaluation suite. We benchmark each version of our embeddings on a diverse portfolio of real downstream applications spanning different problem types:

Binary Classification Tasks: Click prediction for notifications, email engagement, and conversion events.

Multi-Class Classification: User segmentation across behavioral cohorts with varying class distributions.

Ranking & Similarity Tasks: Smart targeting performance where we use centroid-based retrieval.

For each task, we measure both ROC-AUC (how well the model ranks users) and PR-AUC (precision-recall trade-off, critical for imbalanced datasets where positive rates can be as low as 0.1%). To ensure reproducibility and consistency, we automated this evaluation into a benchmarking pipeline. Given a candidate embedding model, the pipeline runs evaluations across all tasks and persists the results, allowing us to track performance regressions and improvements across model iterations. This evaluation framework also allows us to compare the three methods of leveraging embeddings described earlier.

We also find that the pairwise sequence classification outperforms other methods of training self-supervised models:

Masked Token Classification: We randomly mask a token within the sequence and train the model to predict the masked token. We explored multiple masking strategies: (1) uniform sampling across the vocabulary, (2) sampling from the empirical distribution, and (3) adaptive schemes that begin with uniform sampling and gradually increase the frequency of popular tokens as training progresses. We tested both binary and multi-class classification objectives.

BERT-style Pre-training: We trained a standard BERT architecture from scratch using the user action token sequences as input.

Solving Cold Start with User Embeddings

A powerful application of these embeddings is solving the cold-start problem through what we call Smart Targeting.

Imagine we want to send a notification about a newly listed asset. We have no historical data on who likes this specific asset because it's new. Instead of heuristics or using broad targeting, we use an adaptive approach:

Explore: We send the notification to a small, random group of users to gather initial data.

Train: We collect labels (e.g., clicks) and train a classification model, fine-tuning the general-purpose user representation on the specific task.

Target: We use this updated model to identify the next batch of users most likely to engage.

Iterate: This cycle repeats daily. We retrain the model from scratch with the latest labels to mitigate data drift, always including a small random group for continued exploration.

We found this approach more than doubles engagement across many use cases versus hand-designed heuristics. New products typically launch with heuristics and add ML in a later iteration after sufficient data has been collected — but this lets us skip the heuristic stage.

Conclusion

User foundation models improved ML personalization at Coinbase across two dimensions: model performance and development velocity. They drove performance improvements across numerous products and use cases, with experiments consistently showing significant lifts in engagement metrics. The models also dramatically accelerated our ability to tackle new personalization challenges. What previously required days of feature engineering and architecture tuning now takes a few minutes. With a general-purpose representation already in place, building a model for a new use case simply requires collecting labels and training a supervised model—one that reliably outperforms sensible baselines without any custom feature work or hyperparameter optimization.

A major open problem is incorporating time series information. The standard Transformer encoder only captures event order, but unlike natural language, the timing and intervals between user interactions carry significant signal that would require a custom architecture to learn. This is an active area of research at Coinbase, and we look forward to sharing our findings in a future post.